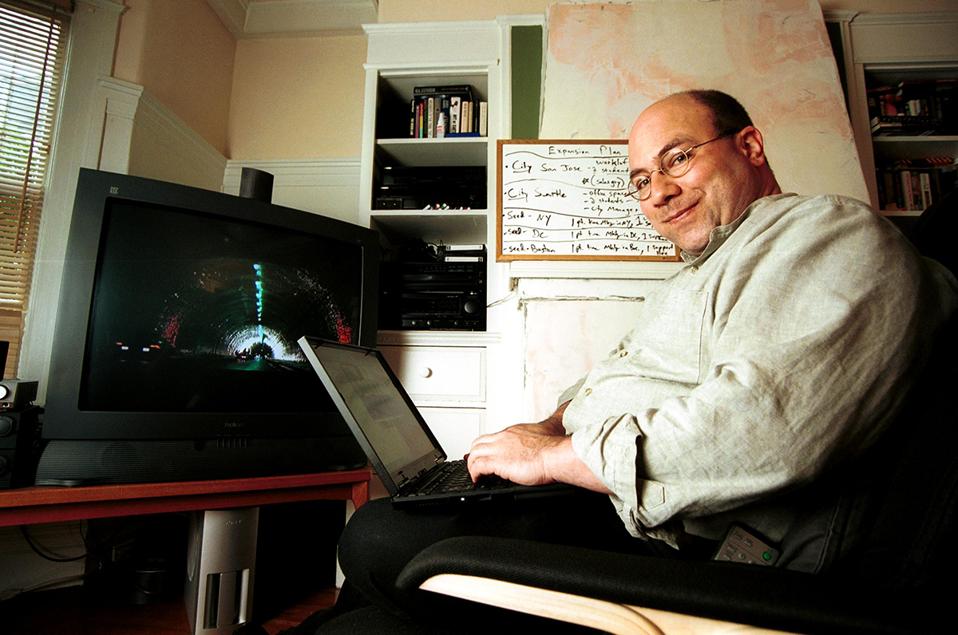

“Itested positive for coronavirus in June, having apparently had the virus asymptomatically,” says Craig Newmark, billionaire founder of Craigslist, via a Google Hangouts video call from his San Francisco home in July. Delivered in his customary monotone, Newmark will only entertain questions about his diagnosis for a few minutes—he got tested because his dentist required two negative tests before an operation. Yes, he has tested negative twice since. He has no idea how he contracted the virus as he rigorously quarantined with his wife, who can be heard chopping vegetables in the background. Then, he moves on. After this call, he says, he will likely treat himself by ordering an anchovy pizza delivery from Bambino’s, a local Italian joint. Perhaps, he adds, he will add pineapple.

Log on to Craigslist today and it feels like a time capsule from 1995, when the World Wide Web was just starting to reveal its purpose. Scroll through the Times New Roman font listings of available apartments or old furniture, and one can almost hear that scratchy alien dial-up modem sound buzzing in the background. Similarly, talk to Newmark and he also feels like a snapshot in time—unchanged and constant through the years, even if he owns at least 42% of a classified ads website that posted an estimated $760 million in revenues last year. Even when the most conservative evaluation of his net worth is $1 billion, based on his Craigslist stake and the hundreds of millions in profits paid to him over the last two decades. And even when he has tested positive for Covid-19, that most contemporary of illnesses.

But on this Monday afternoon, Newmark is not here to talk about his coronavirus diagnosis or his net worth (to which he says, “No comment”). He’s here to talk about misinformation—why he thinks it is destroying America’s democracy and what he’s doing to stop it. Since 2016, Newmark has given $170 million to journalism, countering harassment against journalists, cybersecurity and election integrity. These areas, he believes, are the “battle spaces” of information warfare. The enemy, according to Newmark, are not just foreign adversaries like the Kremlin—it includes the adversaries’ domestic allies. Asked if he views President Donald Trump as one of those domestic allies, Newmark demurs, but suggested Fox News correspondent Chris Wallace’s July 19 interview with Trump as educational material. The interview, which showed Wallace contradicting the President over his claims that America had one of the lowest Covid-19 mortality rates in the world, was called a “master class in how not to let Trump get away with his usual bullshit” by Trevor Noah, comedian and host of The Daily Show.

How will he know that his money has gone to waste? “The people who are in control of this country will be subject to some control by our foreign adversaries and will continue to dismantle our democracy,” says Newmark.

2020 will be a decisive year for Newmark, as it will indicate whether his money has been well spent—or not. Aside from the large gifts to journalism, he also regularly doles out smaller-size gifts to cybersecurity and election integrity. “They’re all parts of the same thing, which is defending our country and protecting the election,” Newmark says. Some recent gifts include $1 million to Global Cyber Alliance, an international computer security nonprofit, $150,000 to national nonprofit Women in CyberSecurity, $1 million to ProPublica for its Electionland coverage, $250,000 to the authors’ nonprofit group, PEN America, to combat disinformation and combat online harassment, and $250,000 to the Girl Scouts to fund cybersecurity programs.

Newmark will deem his donations a success if “we elect a whole bunch of people who want to defend the country, who are honest and who want to fight corruption,” he says. Though he hasn’t publicly endorsed any presidential candidates, he says he has been supportive of politicians with whom he has worked. They include Senator Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), with whom he crossed paths when he worked with San Francisco’s District Attorney; Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), while working with the Consumer Protection Bureau; and Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.), during his work with the Veterans Affairs office. “All three are potential vice presidential candidates, and all three would be great at the job,“ he says.

And how will he know that his money has gone to waste? “The people who are in control of this country will be subject to some control by our foreign adversaries and will continue to dismantle our democracy.”

“I was briefly CEO, until informed that as a manager, I kinda suck,” reads Craig Newmark’s LinkedIn page. At the helm for only ten months, Newmark surrendered the chief executive post to Jim Buckmaster in 2000.

JOHN CHAPPLE/GETTY IMAGES

On the day of the interview, Newmark was particularly worried by what was happening in Portland. Just days before, according to a readout from the Department of Homeland Security, peaceful protests in Portland had grown violent, with alleged anarchists tearing down the perimeter fencing of the Hatfield Federal Courthouse. In response, federal officers were deployed in Portland. President Trump tweeted in defense of the federal government’s involvement in the protests, writing, “We are trying to help Portland, not hurt it. Their leadership has, for months, lost control of the anarchists and agitators. They are missing in action. We must protect Federal property, AND OUR PEOPLE. They were not merely protestors, these are the real deal!”

“The current episode in Portland . . . seems to reflect really bad episodes in world history,” Newmark says. “This has happened in Russia, and it’s part of how Putin got to power. It happened in 1930s Germany.”

The notion that a healthy press is the backbone of a functioning society dawned on Newmark in 1970, thanks to his high school U.S. history teacher in Morristown, New Jersey. “The teacher told us that a trustworthy press is the immune system to a democracy,” he recalls. The idea continued to percolate in Newmark’s mind and, in 2016, with Trump’s election, he felt that democracy’s immune system needed some help. The next year, his friend Jeff Jarvis, a journalist and CUNY professor, told Newmark to read the Handbook of Russian Information Warfare, published by the NATO Defense College’s Research Division. The handbook outlines the strategy of foreign adversaries: Push disinformation into mass media, seek to polarize different groups in the country and get both sides outraged, all with the goal of division, chaos and government destabilization. “That had a pretty big impact on me,” Newmark says.

His largest individual gifts since 2016 have gone to existing and new journalism initiatives. Some have gone well, others awry. In June 2018, Newmark gave $20 million to the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, which renamed itself as the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism after the gift. In February 2019, Newmark gave another $10 million to Columbia Journalism School to launch a new center for journalism ethics and security.

Craigslist is huge, breaking $1 billion in revenues in 2018. It’s estimated that profit margins are close to 85%, with nearly half of that going to Newmark.

He also gave $20 million in September 2018 to fund the creation of a nonprofit news organization called The Markup. Its focus was supposed to be an investigative lens on how Big Tech was really impacting everyday life in America. With a founding team that included Pulitzer Prize winners as well as programmers and data scientists, The Markup seemingly brimmed with promise. But disagreements over the direction of its coverage led to the firing of its editor in chief, Julia Angwin, who complained publicly that the site was being pushed into “advocacy against the tech companies” by one of the site’s cofounders, Sue Gardner, who had previously worked at Wikimedia. Following Angwin’s firing, the editorial staff resigned en masse. And this was all before the website had even launched. (Angwin is now back as editor in chief; Gardner is gone and the website launched in February, about a year late.)

During The Markup’s turmoil, Newmark remained almost completely silent, with only one tweet in April 2019 addressing the incidences: “I am taking this very seriously.” Newmark says his silence was necessary. “The ethics of funding nonprofit journalism are such that I had to not interfere nor help,” Newmark now says. “They also didn’t need my help.” He’s pleased with The Markup’s current output today, he says, and his involvement goes only as far as retweeting any new stories from The Markup. “Sometimes you find good people, you get out of the way, and you let them do their job,” he says.

The irony of Newmark focusing on journalism as one of his core giving areas is not lost on journalists who believe it was his website that took hundreds of millions in revenue away from newspapers, which prior to Craigslist’s founding counted on classified advertising for around 35.6% of their revenue, according to data from the News Media Alliance (formerly the Newspaper Association of America). Newmark’s canned response to this for years has been a reference to media analyst Thomas Baekdal’s research, which showed that newspaper circulation was declining long before Craigslist came around due to cable news. Baekdal also argued that Craigslist was just one of hundreds of online marketplace websites taking advertising revenue from newspapers, from eBay (founded the same year as Craigslist) to Autotrader.com (founded two years later). In 2018, the New York Times, which called Newmark a “newspaper villain,” reached out to Baekdal. He wrote back, “If I were to imagine a world where Craigslist was never invented, I do not think it would have made any difference.”

Newmark started Craigslist in 1995, two years after moving to San Francisco from New Jersey and with 17 years of computer programming experience at IBM under his belt. At its founding, Craigslist was a curated list of San Francisco events that Newmark emailed to friends and colleagues. He soon turned it into a listing site, and users quickly started using the website to sell all kinds of goods. To monetize, Newmark decided some listings—jobs, real estate, cars—would require a fee, ranging from $7 to $75, but the majority would be free for users.

Craigslist to A-list: Newmark shakes hands with actress Lena Dunham at the Time 100 Gala in 2013 and rubs shoulders with comedian Stephen Colbert at the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America’s Heroes Gala in 2018.

In 1999, Newmark was CEO for a brief ten months, before he gave the job to Jim Buckmaster, who remains CEO to this day (Buckmaster did not respond to requests for comment). While Newmark still retains a large stake in the company, he has relegated himself to a “customer service rep,” according to his LinkedIn page, and says he is no longer involved in the day-to-day operations of Craigslist. The site is huge, breaking $1 billion in revenues in 2018, according to Peter Zollman, an analyst at classified ads research firm AIM Group, though that figure dropped 27% the next year due to a decline in job ads as well as growing competition from VC-funded sites like OfferUp to tech juggernauts like Facebook Marketplace. Still, with fewer than 50 employees and low overhead costs, Zollman estimates that profit margins are close to 85%, with nearly half of that going to Newmark.

On July 29, after weeks of increased presence, federal officers agreed to withdraw from the city of Portland. “They have acted as an occupying force & brought violence,” Gov. Kate Brown of Oregon said in a tweet. The next day, President Trump jumped on the Twitter soapbox as well and declared that mail-in voting will be “INACCURATE & FRADULENT” and suggested delaying the election. Newmark continues to watch from his home. He’s tweeting and retweeting prolifically, sharing news stories on election misinformation and journalism ethics or announcements of new charitable gifts. He’ll often tweet a photo of a bird (he’s an avid birdwatcher). Occasionally, his wife will make an appearance: “Mrs. Newmark complains that a squirrel is eating the blueberries from our plants . . . ”.

No matter what happens in November, one thing is certain: Newmark will continue doing what he’s been doing for years. “I have a lot of cash that I’ll still be giving away as my twilight years progress,” Newmark says, who will turn 68 in December. He will continue giving to journalism and cybersecurity for the foreseeable future, he says, but he’s got a few other passion-giving areas as well, including $100,000 to wildlife rescue and “in the low hundreds of thousands” in relief funds to comedy clubs that have been closed during the pandemic. “Sometimes, I’ll make a funny exception,” Newmark says, unflappable as ever.

Source: forbes.com

Be the first to write a comment.